donated by

Bruce E. Newcomb & Karen kullas

Military Uniform of the XI (Eleventh) Regiment Massachusetts line, Continental Army

By Bruce E. Newcomb

The dress military uniform consists of a regimental coat (blue), westcoat (light gray), shirt (cotton), pants (canvas), leg straps (leather), officer’s sash (red), tricorn hat, silk stock for neck, and shoes with buckles. The waist belt will hold a sword and scabbard (a protective covering for the sword). The field uniform consists of a hunting frock (natural color burlap), shirt (cotton), pants (canvas), leg straps (leather), tricorn hat, leather stock for neck, and shoes with buckles. The brown hair wig with queue represents the typical hairstyle of the era. The white hair wig was worn for formal occasions. The Polearm is a long weapon, with a metal spear point, used in battle. During the Revolutionary era, the Polearm became more ceremonial and was used in formal military presentations. The waist belt is an accoutrement for formal occasions to hold the scabbard and sword.

Details of the articles of clothing:

The REGIMENTAL COAT is wool material in medium blue, with white lapels. The white color of the lapels is specific for Massachusetts regiments. The buttons are pewter, cast at Reed & Barton in Taunton MA in 1974. The insignia on the buttons is Roman numeral eleven, “XI”, signifying the Eleventh Regiment. The tails of the coat would have been secured upward, revealing the touching hearts, which is emblematic of King Richard the Lionhearted.

The WESTCOAT (a vest) is wool material in light gray. The buttons on the vest are pewter and also contain the Roman numeral eleven, “XI”, signifying the Eleventh Regiment.

The SHIRT is cotton and typical of those worn in this era. Cufflinks (wooden buttons) would have been typical to secure the sleeves of the shirt to the person’s wrists.

The HUNTING FROCK is a natural color burlap material and is an enlisted man’s field uniform with a capelet to offer protection from the weather.

The PANTS are white canvas, and have leather LEG STRAPS to secure them from snagging on bushes, etc.

The OFFICER’S SASH in red wool material was worn to delineate that they were an officer versus an enlisted man.

The SILK STOCK is worn around the neck with the dress uniform.

The LEATHER STOCK was worn in battle to prevent neck wounds from swords or knives.

The TRICORN HAT is worn with the front point over the left eye, to allow clear visibility on the right side when firing a musket (firearm). This hat also has a cockade on the left. The cockade is a rosette or knot of ribbons, in black; the white ribbon was added to the cockade to show the alliance between the French and the colonies.

The WAIST BELT is made of leather and has a fitment attached to it, which will hold a scabbard and sword. The shoes are typical of the era. An enlisted man may have worn shoes that were neither left nor right and were merely broken in for a particular foot.

The Reenactors in action

The photographs below depict two major events that transpired leading up and during the American Bicentennial Celebration of 1976.

Photograph One (1) is of a ceremony of then Governor Michael Dukakis as he signs a Proclamation reactivating the XI (Eleventh) Regiment of the Massachusetts line of the Continental Army.

Pictured from Left to Right are Lieutenant Philip Paulson, Private Joseph Cavaco, Private Ralph Fontaine, Major Bruce Newcomb, Senator John Parker (R-Taunton), Governor Michael Dukakis (seated).

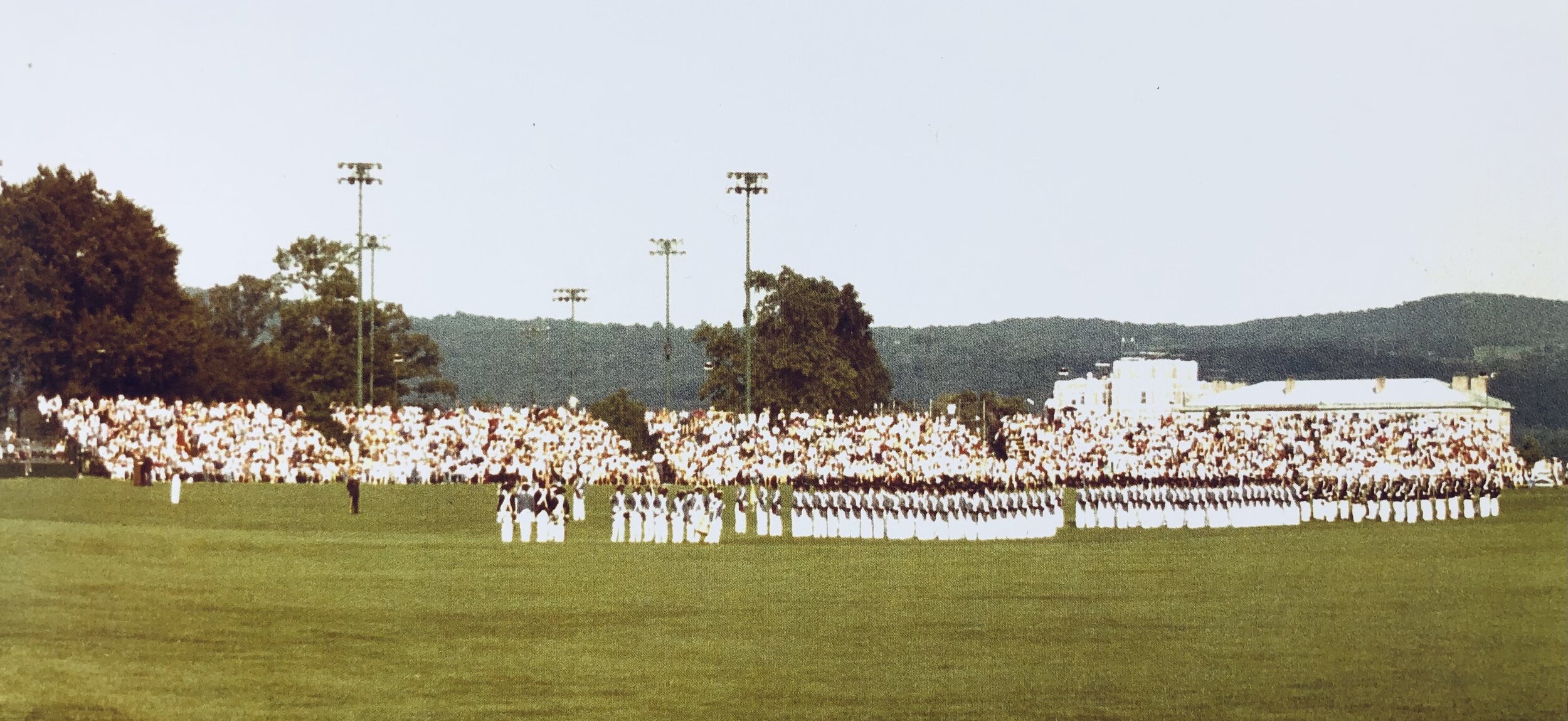

The remaining photographs were taken on July 4, 1976, when the XI Regiment occupied Fort Putman, at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York.

Pictured is the XI Regiment participating in the official ceremony commemorating the Bicentennial, on the “Plain” at the U.S. Military Academy. Also participating are the Cadet Corp and the Cadet Band of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point.

Additionally, there are pictures of the XI Regiment providing guidance and information to the visitors at Fort Putnam.

We also received a wonderful account of this regiment. Click here to read “The Story of the XIth Regiment of the Massachusetts Line of the Continental Army”.

by philip D. Paulson

“BRITISH REVENGE”

Upon arrival at Fort Putnam, July 4, 1976, I was advised as “Commanding Officer of the Day” of the XI Regiment, that during the early morning hours of July 4, 1976, two British Officers attached to the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division and on TDY (Temporary Duty) from their British Black Watch division, had scaled the wall of Fort Putnam and raised the British “Union Jack” flag over the Fort.

Without fanfare and discreetly and with all military protocol, the “Union Jack” flag was lowered by a military contingent from West Point. (READ MORE about this amazing event below)

Respectfully submitted,

Bruce E. Newcomb

On 4th July, Bicentennial Day 1976-A Union Jack, not a Star Spangled Banner flew over the US Military Academy West Point! How Come? July 4, 2020

July 4, 2020 montrose42 Uncategorized4 July 1976, bicentennialatweStpoint, fort putnam, union jack at west point, USMA, west point military academy

At Muster Parade, 4th July, 1976 (America’s big Bicentennial birthday), at WestPoint US Military Academy, a Union Jack, not a star spangled banner, flew proudly over the ramparts of Fort Putnam, overlooking the parade ground, as the officer cadets assembled. Attached to the base of the fort’s flagstaff, was placed a note. It read ‘It’s taken us 200 years, but we are back ‘Two British officers had put it there, earlier that morning, just before dawn. I was one of them.

As the cadets, began, in disciplined silence, to shuffle into regular lines, for the morning ritual, they were watched ,at a discreet distance, by me and Mike Reynolds, a British officer from the Kings Own Scottish Borderers, on attachment, at the time, to the Academy’s instructing staff. It wasn’t too long before someone in the ranks, eyes elevated , did a double take, and clocked that something was not quite right. Whispers, rippled through the ranks , heads bobbed, and there it was, a resplendent, ‘come and get me’ provocation, fluttering in the breeze .It was a deeply satisfying moment .Payback time, after 200 years of hurt.

Bicentennial year hadn’t been an easy one, if you were a Brit, in America. We had had to put up with a lot. Endless battle re-enactments, and endless fifes and drums. And then there was the re-writing of history. George Washington wasn’t, for the record, a general on a par with Napoleon. Arguably, he wasn’t really a general at all. The continental forces, aided in no small measure by France, still bristling from its defeat by the British in the Seven Years war, ultimately won, of course. But we should not forget that American forces were defeated in battle by the British on a ratio of three to one, in favour of the British. When I say the British, more accurately I should really be saying the Germans. Mercenaries from Hesse, Hanover and elsewhere, in what is now Germany, were brought in to do most of the fighting. They say that the victors write the history, it was ever thus. Challenging the American narrative at the time though, would have been impolite, bordering on rudeness So the Brits role had been to suck it all up, without complaint.

I really shouldn’t even have been at West Point, that summer. I had won an army scholarship to University. Part of the deal, in return for the Ministry of Defense paying my tuition fees and giving me a not ungenerous salary at university during my three years of study, was to spend a month training with my regiment each year. Luck would have it that that summer, my regiment, the Black Watch, was deployed in Northern Ireland, on an emergency operational tour. The province was quite lively at the time. Bombings and shootings were commonplace. Because of my lack of serious basic training-the full Sandhurst Officers Course came after graduation, not before – I, along with other undergraduate officers, was not permitted to go anywhere near Northern Ireland, for our own safety, and indeed, it’s safe to assume, for everyone else’s.

The obvious alternative option was to be attached, instead, to another Scottish regiment, for a month. This did not appeal much, as, at the time that would have meant either Germany, or Scotland.

Fortunately, my father, as luck would have it, was the British military attaché, in Washington DC. He was a busy man in 1976. Apart from various military tattoos, that involved contributions from our great military bands, and of course our pipes and drums ,he had to manage increasingly deluded requests from the American military ,and battle re-enactment groups, for British soldiers to dress up in eighteenth century uniform, in order to surrender to American militiamen He busied himself with managing the Americans expectations, rapidly downwards .

After some discussion, my father suggested an attachment to West Point Military Academy , roughly Americas equivalent to our own officers training institution at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst ,although the respective institutions philosophies differ somewhat .West Point is beautifully situated in New York state , on a bend of the Hudson River and an easy drive to New York city, which was helpful.

As a sweetener, to seal the deal, for West Point to take on an undertrained student officer, my father persuaded his, and my, regiment, the Black Watch, to part with an experienced piper to help tutor West Points pipe band

. It all worked out well enough. It helped that the Black Watch was well known and popular in the States. Even to the extent that Jackie Kennedy had insisted that a Black Watch piper played at her husbands (JFK) funeral. The piper chosen for this attachment, Corporal Rafferty, would later become Pipe Major of the Black Watch.

So, in late June 1976, I found myself standing on West Points parade ground (The Plain) with Corporal Rafferty to begin the joint attachment .The idea was that I would support the directing staff there in running the cadets basic training and assessment over the four weeks, that included section and platoon attacks, patrolling and ambushing.

For the duration of my stay I was billeted with a company of the tough as teak ‘82nd Airborne, or ‘the eighty deuce’ .They were a no- nonsense, elite unit, with a fearsome reputation, most recently reinforced through their exploits in Vietnam .(The Vietnam War had ended in 1975) They were the demo troops to put the cadets through their paces, acting as enemy during summer training and assessment . To be frank, I was a little apprehensive at the prospect. After all, I was a student and, although I had done some physical preparation for the attachment, I realized it was probably never going to be remotely sufficient to meet the Airborne’s stellar fitness standards. I had also been told that I would be doing everything they did. They were true to their word.

I shared a room with young platoon commanders, mainly southerners, who couldn’t have been more welcoming or supportive. The limey in their ranks was for them, it seemed, both a curiosity, and a diversion. We bonded, over the month, exploring the Big Apple, and its more seedy underbelly.

After the 82nds reveille, each morning, we assembled for the Company run, in tight formation. I was relieved when the troops had a caller who would start singing “Here we go all the way.. got to be rough and tough, Airborne all the way..,” or some variant . Singing and running are not easy bedfellows, so although the pace was always testing, it was manageable. The run was routinely followed by other strenuous exercises to kick start each day rounded off with 100 press ups.

Above West Point and the Hudson River, stands Fort Putnam dating from revolutionary times. It overlooks ‘the Plain’. Like any Fort Worth its salt, Putnam had thick defensive walls, but they were not particularly high, certainly in some places around its perimeter. This observation sparked the kernel of an idea.

Mike and I had to come up with a plan of what to do on the big day. We couldn’t just sit on our hands watching West Pointers celebrate and gloat. So, on the evening of the 3rd of July 1976 , after supper, and having downed half a bottle of Mike’s best Malt Whisky, we jointly hatched a plan.

We knew that early morning West Point cadets assembled on the Plain, for Muster parade at a fixed time. Whatever, we did it had to be witnessed by as many cadets and staff as possible and preferably at the same time. It had to have legs, and last for more than a few minutes. And it had to be an obviously British gesture, significant, but without being seen as insulting to our generous hosts.

Americans, we knew, loved and respected their flags, badges, symbols and ceremonies. We just needed to find a Union Jack that was sufficiently large and in good enough condition to do us proud. Not forgetting, of course, a long extension ladder. Fort Putnam’s gate was secured at night, and so we would have to scale its eighteenth century walls.

The early hours of 4th July saw us on a mini treasure hunt, in search of a flag and long ladder. Miraculously, we found both, quickly (s far as the union jack was concerned, remember there were battle re-enactments going on). We then scoured a map of the Academy grounds, planned approach routes and timings, taking into account, of course West Points security system-static sentry posts and mobile patrols. We worked out where the guard posts were, and a circuitous route around them and the mobiles routine. If we were challenged, the plan was to dump the ladder, but keep hold of the flag, split, running in opposite directions and RV at an agreed, predetermined spot. There, to regroup, and, if need be, to try again.

Raising flags, to the uninitiated, can be awkward. Speed is not the essence. Take it slowly or it will jam halfway up the pole. Mike, thankfully, claimed more expertise in this area than I So, I kept Cave and had responsibility for the worryingly rickety extended ladder, ensuring that it was sufficiently stable for Mike to climb. Because of vehicle patrols we couldn’t be around for more than 10 minutes, once we had the ladder against the forts wall. Mike had to be up and down the ladder in a flash.

Once the flag was up, the Americans couldn’t simply take it down, and raise the Stars and Stripes. There were formal protocols to be observed, in lowering a nation’s flag. We knew this. So, the Union Jack fluttered above West Point on 4th July 1976 for several hours until a military detachment formally lowered it, with due ceremony.

We were not entirely sure how West Points staff and cadets would react to it all. In the event, they were marvelously good humoured, and took it all in the spirit that was intended, warmly congratulating us for our efforts.

Note

A few years ago, I came across John Keegans‘ Fields of Battle: The Wars for North America’. Buried deep in its pages was a brief account of this incident but with no names attached. So, in a sense, this is an exclusive.